Family Origins - McGregor

Family Origins - McGregor

M

cGregor is an ancient Scottish clan name and the principal of over 100 recognized names, septs, and aliases of the Clan Gregor.1 Volumes have been written about the myths and legends of the McGregors, as well as the equally fascinating historical facts that form the clan’s rich heritage. McGregor history spans centuries of royalty, affluence, prosperity, disfavor, persecution, warfare, proscription, infamy, and finally, normalcy.

We have traced our branch of the McGregor family to one William McGregor who was born c. 1780 and who lived in Dunfermline, Fifeshire, Scotland. Two of his descendants immigrated to the United States in the late 1800s; they are our direct immigrant ancestors.

In this document we attempt to answer the following questions:

- What is the origin of the McGregor name and clan?

- Are we related to the famous Rob Roy MacGregor?

- How did our branch come to settle in Dunfermline?

First, let’s clarify the significance of the prefix Mc. Prefixes similar to Mc, Mac, and M’ all mean ‘son of.’ Contrary to what some people may have heard, these prefixes are completely interchangeable, and none indicates any particular place or country of origin. Usage of one prefix over another simply follows a family’s or individual’s preference or tradition.

What does Gregor mean?

Gregor and Gregory are English forms of the Greek name Gregorios meaning “watchful” or “vigilant,” which is derived from the Greek word “egeirein” meaning “to awaken.” The verb “egeirein” and several variants appear in the Ancient Greek version of the New Testament to express resurrection from death and Jesus’ own resurrection. The Greek name passed to the Late Latin Gregorius. The name was introduced to the British Isles with Christianity and translated to the Scottish Gaelic Griogair. The name became common in Scotland and England only after the Norman conquest in 1066.

Who was Gregor?

McGregor literally means ‘son of Gregor.’ However, the exact identity of ‘Gregor,’ the Clan’s namesake, is the subject of much historical debate. The Clan Gregor traditionally traces its roots to Griogar (Gregor), thought to be the third son of King Alpin II. Modern scholars agree, however, that evidence is lacking for the existence of this third son. Others suggest the namesake ‘Gregor’ could be Griogair, son of Dungal, who ruled from 879 to 889 in Alba, the Celtic name for Scotland. Still other historical figures are claimed by various groups as the clan’s original ‘Gregor.’ Despite the conviction of these various claims, the truth is that records no longer exist that can prove conclusively the identity of the clan’s namesake. Knowledge of the early kings of Scotland before Malcolm II (954–1034), the last king of the House of Alpin, is mainly legend. Most of the early Scottish public records were destroyed by order of the English King Edward Plantagenet, during his occupation of Scotland at the end of the 13th century.2 A few medieval records, written by Irish and Welsh scribes, apparently contain accounts of early Scottish kings and related events, although these documents were written centuries after the reported events, and the details have been inferred from indirectly written prose. The lack of contemporary evidence, ambiguities in the few existing medieval records, and retelling of oral histories over generations, all serve to explain the variations found in modern literature and web sites regarding names and relationships among these medieval people, and the uncertainties in dates, locations, and details of various historical events.

House of Alpin

Most scholars agree that the Clan Gregor originated from the royal House of Alpin. Ailpín mac Eochaid, known as King Alpin II of Dalriada (755?–834), sometimes called Alpin of Kintyre, King of Scots, was the 28th and last of the long royal line of Dalriadic Scots. Dalriada (in Celtic: Dál Riata) is a region of Scotland that includes modern day Argyll, Kintyre, and various west-coast islands.

King Alpin II’s ancestry is uncertain; experts disagree on the identity of his parents because of conflicting data in various medieval records. It is generally accepted that King Alpin II ruled from 832 to 834 and that he was killed in 834 in Galloway, in the southwest corner of Scotland. (Some sources say he died in battle near Dundee fighting the Picts but this has been largely discounted as fiction.) The Picts were the native peoples of Alba, and mostly occupied the lands to the north of Dalriada. Centuries of warfare between the Picts and the Scots, along with intermarriages and alliances, had temporarily consolidated the Pict and Scot thrones for a few brief periods. Both groups were threatened by the Vikings from the north and west.

According to most historians, King Alpin II had two sons, Cináed mac Ailpín, known as Kenneth I (810–858), and Domnall mac Ailpín, known as Donald I (812–862). Kenneth I succeeded his father King Alpin II in 834 which led to Kenneth’s title as King of Scots, i.e., of Dalriada. Meanwhile, to the north, Viking raids in 839 had killed off most of the Pictish royalty and left the crown vulnerable to takeover. In 841 Kenneth attacked and defeated the remainder of the Pict army.

It should be noted that succession to the Scots throne was through male lines, whereas the unusual Pict tradition was through matrilineal succession. Kenneth’s mother was of Pictish descent from the royals who ruled Fortrenn (a region to the west of Perth) and so provided him (as well as other nobles) with a claim to the Pictish throne. In a legendary incident called MacAlpin’s Treason, Kenneth held a great banquet at Scone to which he invited the reigning Pictish King Durst IX and the seven nobles who had claims to the Pictish throne. Much drinking ensued, and once the Pictish guests were drunk, Kenneth’s Scots opened concealed chambers beneath the benches, the chambers being lined with blades. King Durst and all of the nobles fell into the chambers and were either killed directly by the blades or by the Scots from above.3 Thus, in time Kenneth was able to claim the Pictish throne. Although he was not the last King of the Picts, it is generally accepted that Kenneth was the Scottish ruler who started the eventual unification of Scotland, i.e., the unification of the Picts and the Scots. For this reason, Kenneth is regarded as the first Scottish king. Kenneth’s undisputed legacy was to produce a dynasty of rulers who claimed descent from him and ruled Scotland for much of the medieval period.4

Kenneth died in 858, it is said due to a cancerous tumor. He was succeeded by his brother Donald, who ruled from 858 until he died in 862. He was followed by a succession of Scottish monarchs from the House of Alpin down to Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, known as Malcolm II (954–1034). Because he had three daughters and no sons, Malcolm II was the last of the House of Alpin.

Sìol Alpin

Sìol Alpin (from the Gaelic Sìol Ailpein, or Seed of Alpin) is a group of seven Scottish clans who all claim descent from King Alpin II. The seven clans are Clan Gregor, Clan Grant, Clan MacAulay, Clan Macfie, Clan Mackinnon, Clan Macnab, and Clan MacQuarrie. Clan Gregor is considered to be the senior clan. The clans of Sìol Alpin share many stories and traditions, including various alliances between clan chiefs during times of strife and warfare, all strongly suggesting family ties through a common Alpin ancestor. Remarkably, all seven clans share a common plant badge, the Scots Pine.5

DNA Evidence

Expert interpretations of cryptic medieval records, combined with oral histories, myths and legends, all provide convincing, if circumstantial, evidence for the House of Alpin as the true origin of the Clan Gregor. Strong evidence also comes from scientific DNA techniques.

DNA testing has become an important and highly reliable genealogical tool, and generally involves comparing the results of living individuals to historic populations. Females carry two X chromosomes whereas males carry one X and one Y chromosome. The Y chromosome (Y-DNA) passes from father to son virtually unchanged for many generations. A person’s matrilineal ancestry can similarly be traced using the DNA in the person’s mitochondria (mtDNA), which is passed from the mother, unchanged, to all children.

The Clan Gregor DNA Project has, since 2001, analyzed the DNA of over 480 participants using both Y-DNA and mtDNA samples.6 The results support a preliminary conclusion that the clan traces to the Dalriadic royals, e.g., the House of Alpin. This is consistent with DNA results of other Scottish clans who claim a similar descent. The Clan Gregor Y-DNA data does not support the contention, discussed earlier, that the family may trace to Dungal, a ruler in Alba.7

Clans and Clan Chiefs

Historians agree that the clan system began forming in the 11th century, about the same time as Scotland’s unification. The clan system was an effective form of government in the Scottish Highlands. A clan was headed by a chief who wielded absolute power over his clan and to whom his clansmen were fiercely loyal. The clan members included the chief’s children and other blood relatives, and also included unrelated people who lived in the same vicinity and relied on the clan chief for protection. A clan traditionally occupied a specific territory, and as a clan’s numbers grew, the clan sought to expand its lands in order to thrive and prosper.8

Although other individuals provided leadership to the clan, the Clan Gregor Society lists their first chief as Griogar of the Golden Bridles (1300?–1360?). Four primary families descended from Griogar are of Glenstrae, Glencarnaig, Roro, and Glengyle. The succession of chiefs that followed came from the Glenstrae branch, which died out as a result of decades of persecution. Afterward, the clan chief switched among the other three families.9

The progression of Gregor Clan chiefs is, with a few exceptions, generally well supported by credible records. The current and 24th chief is Major Sir Malcolm MacGregor of MacGregor, 7th Baronet, who is descended from the Glencarnaig branch.

Glenorchy, Homeland of Clan Gregor

Early family members trace to Glenorchy, a few miles to the northeast of Dalmally at the head of Loch Awe in the heart of historical Argyll. Hugh of Glenorchy is the first member of the Clan Gregor who is documented as being from Glenorchy. His name is listed in the epic tome Book of the Dean of Lismore, a manuscript collection of poetry, obituaries and other writings collected and published by Sir James M’Gregor, Dean of Lismore, in the early 16th century, many apparently from original documents, now lost.

Detailed translations and analyses of his work have been undertaken, one of the most notable titled The Dean of Lismore’s Book, published in 1862 by Rev. Thomas M’Mauchlan with additional notes by William F. Skene.10 The Book includes a genealogy of the MacGregor clan from King Alpin through John dow M’Patrick M’Gregor of Glenstrae, who died in 1526. “Hugh of Urquhay,” as his name appears in M’Mauchlan’s translation, is included in the genealogy. And while modern analysis has identified the genealogy to be somewhat incomplete (certainly missing some generations between Hugh of Urquhay and Kenneth Macalpin), it provides the earliest known mention of a member of Clan Gregor being “of Glenorchy.”

The Clan Gregor was granted land in Glenorchy by King Alexander II (1214–1249), for services the clan rendered during the conquest of Argyll, although it is unclear whether Hugh of Glenorchy or another member Clan Gregor was the recipient.

Persecution and Proscription

Clan Gregor suffered severe misfortune beginning in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, while the Campbell Clan, also seated in Argyll, was gaining both power and territory. The Campbells progressively usurped MacGregor lands, either by royal proclamation (such as land grants and charters by Robert the Bruce and by David II) or by force. By the mid-1400s, the MacGregors had lost all ownership of their lands in Argyll including their ancestral Glenorchy holdings. The MacGregors were driven into hiding, being called the “Children of the Mist,” and became outlaws. They resorted to plundering their neighbors’ lands in order to survive, which in turn increased the oppression against them. Various Acts of Privy Council were passed to pursue the Clan Gregor with fire and sword. Still, the MacGregors persisted in their efforts to survive, resorting to increasing levels of violence, which was answered by more persecution. Numerous acts of ruthless and systematic brutality against individuals and groups of MacGregors during the 16th through 18th centuries are documented in contemporary accounts and retold in countless history books and websites, so the extensive details are not presented here. It is, however, important to recognize that the legal (if not moral) justification for nearly 175 years of persecution against the Macgregors was provided in the infamous Acts of Proscription, as they are informally called.

In The Highland Clans, Volume II, by William F. Skene in 1837, Skene provides a concise summary of the Acts:11

“By an Act of the privy council, dated 3d April 1603, the name of Macgregor was expressly abolished, and those who had hitherto borne it were commanded to change it for other surnames, the pain of death being denounced against those who should call themselves Gregor or Macgregor, the names of their fathers. Under the same penalty, all who had been at the conflict of Glenfruin, or accessory to other marauding parties charging in the Act, were prohibited from carrying weapons, except a pointless knife to cut their victuals. By a subsequent Act of council, death was denounced against any persons of the tribe formerly called Macgregor, who should presume to assemble in greater numbers than four. And finally, by an Act of Parliament 1607, c. 26, these laws were continued and extended to the rising generation, in respect that great numbers of the children of those against whom the Acts of privy council had been directed, were stated to be then approaching maturity, who, if permitted to assume the name of their parents, would render the clan as strong as it was before. The execution of these severe and unjustifiable Acts having been committed principally to the earl of Argyll, with the assistance of the earl of Atholl in Perthshire, were enforced with unsparing rigor by that nobleman, whose interest it now was to exterminate the clan; and on the part of the unfortunate Macgregors were resisted with the most determined courage, obtaining sometimes a transient advantage, and always selling their lives dearly.”

In 1604, shortly following the initial Act, the clan chief, Alexander, Macgregor of Glenstrae, was captured and hanged in Edinburgh, along with 30 of his warriors. Other prominent Macgregors suffered a similar fate. Family members adopted other surnames including Graham, Grant, Murray, Stewart, and Campbell (despite the Campbell clan being the Macgregor clan’s principal persecutors). The acts of proscription were rescinded in 1661 but were reinstated in 1693 until the proscription was finally abolished in 1774. It is speculated that, because of the proscription of the name Macgregor, only true Macgregors resumed their former surname, making the clan one of the purest. And there is no way to know how many Macgregor individuals kept their adopted name instead of reclaiming their birthright surname. In either case, the proscription presents a severe obstacle to the ability of modern Macgregor family historians to trace their ancestry much before 1800, because few records document the change of a family’s name at the end of the proscription.

Fifeshire and Dunfermline

Dunfermline is the third largest town in Fifeshire, and is situated five miles inland from the north shore of the Firth of Forth. Historical records indicate the first settlement at Dunfermline was around 506 AD. Malcolm III established Dunfermline as the seat of royal power in the mid-11th century, and the town served as the de facto capital of Scotland into the mid-15th century. Dunfermline continued its royal connections to the beginning of the 17th century. Malcolm’s second queen, Margaret, persuaded her husband to build a Benedictine priory in the royal center, which in 1128 became Dunfermline Abbey. The abbey church was sacked in 1560 and much of the remaining structure fell into disrepair. A major fire in 1624 left a large part of the medieval-renaissance burgh in ruin. A new church built using surviving parts of the abbey opened in 1821. Parts of the original abbey infrastructure remain, and next to the abbey is the ruin of Dunfermline Palace. Many of Scotland’s royals were born, married, or buried in Dunfermline Abbey, most notably Robert the Bruce, whose body was buried in there in 1329, although his heart was taken for burial to Melrose.12

A few years after the initial enactment of the Acts of Proscription of the Macgregor name and clan, other acts were proclaimed that provide an interesting connection between Macgregor individuals and Fifeshire. The History of the Clan Gregor, by Amelia Georgiana Murray MacGregor, first published in 1898, provides extensive details of the Acts, many shown in their entirety.13 From MacGregor’s History, pages 382-83, one Act dated 24 May 1611 at Edinburgh reads:

“The Lords of Secret Council for the better furtherance of his Majesty’s service against the ClanGregour give power and commission to Archibald Earl of Ergyll his Majesty’s Lieutenant, Justice, and Commissioner against the ClanGregour to charge such persons within the Sheriffdom of Perth whom in his honour and conscience he shall think to be favourers, resetters, or assisters of the ClanGregor to transport themselves to the Sheriffdoms of Fife, Stirling or Forfar and to remain there for the space of two months.”

Also from MacGregor’s History, page 391, an order of His Majesty’s Secret Council written in November 1611 to the Earl of Argyll makes allowances for a sort of safe haven for MacGregors in Fife and requires them to redress any wrongs they have caused to the extent they are able:

“The conditions of the caution to be founden by the McGregouris who are to be received in favour.

“That they shall be answerable and obedient subjects to our Sovereign and his laws, That they shall satisfy and redress all parties who shall sustain harm or skaith of them hereafter and for bygane wrongs that they shall make redress so far as they have geir, That they shall not assist nor take part with the ClanGregor, reset them, their wives, bairns nor goods nor keep conventions, trysts nor meetings with them, by word nor write, That they shall remain and keep ward within the Sherrifdom of Fife or any part besouth the waters of Forth and shall not resort, nor repair, benorth the said water, and last that they shall compeir personally before his Majesty’s Council so oft as they or their cautioners shall be charged to that effect. Upon ten days warning under such pecunial sums as shall be modified by his Majesty’s Council to be paid to his Majesty, in case they fail in any part of the premises besides the satisfaction and redress of the parties skaithed.—Record of Secret Council.”

The following definitions of several old English terms should help clarify these acts and orders:

- Bairn: A child, or a person who is dependent on another person

- Compeir: Modern spelling: compear [Scottish]: to appear personally in court

- Forfar: The former name (Forfarshire) of the county of Angus

- Geir: Belongings, possessions, or goods

- Pecunial sums: Monetary fines

- Resetter: Receiver of stolen goods

- Sheriffdom: The region that is presided over by a sheriff. In times prior to 1700, sheriffdoms were hereditary, and were subject to frequent changes in boundaries. They correspond approximately to the Scottish shires or counties.

- Skaithed: Harmed, injured

One example of a McGregor resettlement is documented in the Journal of the International Music Society 1904-05, Volume 6-7, page 244 (the journal is written in German although this article is in English):14

“A correspondent has written as follows to the “Glasgow Herald” regarding the Macgregor ancestors of Edvard Grieg, who is about to make concerts in London on 17th and 24th May next: —

“It is very generally known that the great Norwegian composer is of Scottish descent, but few perhaps are aware that his ancestors belonged to the unfortunate Clan Macgregor. In 1611 James VI., driven to despair by the deeds of violence and turbulence of this clan, gave orders to the Earl of Athole that the most troublesome amongst them should be driven down from the mountains of Perthshire and forcibly “planted” in the towns and villages along the coast of Fife, Forfarshire, and Aberdeenshire. In the above-mention year a certain couple, compelled under pain of death to abandon their own name of Macgregor, were settled in the village of Kennoway, in the former county, under the name of Grig. The story of the descendants of these aliens may be traced in the pages of the kirk session records of Kennoway Parish. From generation to generation they are to be found being baptized, or married, or buried — worthy farmers most of them, or small lairds, some of them elders of the Church. In course of time these Grigs, apparently dissatisfied with the startling abruptness of their assumed surname, added a final “e”, which was transferred by future members of the family to the middle of the word — thus, Grig, Grige, Greig. One of these Greigs of Kennoway, Charles by name, migrated to Laverkeithing, and was the father of the Admiral so greatly honoured by the Empress Catherine of Russia; whilst another branch of the family settled in Peterhead. One of these last, Alexander Greig, a fugitive from the gallows after the Jacobite rising of 1715, by a fortunate chance managed to escape with his spouse, Anna Mylne, in a vessel bound for Bergen in Norway. From this couple is descended the famous Edouard Grieg. The Griegs in Norway have always been able to trace their pedigree back to the Jacobite, Alexander of Peterhead, and in recent years they were much interested to learn from a Scottish minister visiting their country of the Macgregor descent, a story preserved amonst numerous Greigs, Ballingals, Russels, and others connected with the Kingdom of Fife.

It appears, then, that some McGregors were resettled as early as 1611 to Fifeshire and nearby counties, outside of the historical Macgregor territory. This provides a possible explanation for how our McGregor family came to settle in Dunfermline. Further research may uncover evidence to support this conjecture and extend our McGregor family’s history.

Rob Roy

It is common for modern McGregor families to claim a connection with the Scottish folk hero and outlaw Rob Roy MacGregor (1671–1734), whose exploits are the subject of both legend and history and are well documented in both contemporary and modern literature (so the details are not presented here). Our McGregor family is no different in making this claim. However, it is extremely doubtful that we have any direct connection to Rob Roy.

Rob Roy often used the surname Campbell (from his mother Margaret Campbell) since the Acts of Proscription banned the use of the Macgregor name during much of his lifetime. Most of his male descendants are found under the MacGregor surname. His wife, Mary Helen MacGregor of Comar, bore him four sons: James (known as Mor or Tall), Ranald, Coll, and Robert (known as Robin Oig or Young Rob). A cousin, Duncan, was later adopted. Rob Roy’s descendants are well documented at least into the 1800s in the highlands of Scotland, and in some cases to current day in Scotland, the United States, and elsewhere. None of Rob Roy’s descendants are known to have lived in the Scottish lowlands, and particularly in or near Dunfermline or nearby towns in Fifeshire where our McGregor family lived.

Our McGregor Family in Scotland

We have reliably traced our McGregor family to David McGregor (c.1812–1898), who married Janet Sinclair (c.1809–1887), and who were lifelong Dunfermline residents. We believe David’s parents were William McGregor (c.1780–?) and Betsy Thom (c.1780–?), their birth years estimated from their marriage entry shown in Fifeshire parish records as 1797. Since none of Rob Roy’s documented descendants bear the names David or William down through at least 1800, it therefore seems unlikely that our McGregor family is directly related to Rob Roy.

Our Scottish McGregors were weavers, which was a prominent trade and industry especially in Dunfermline in the 18th and 19th centuries. Weaving of fine damask linen was introduced in 1718 which led to Dunfermline becoming the world’s leading linen producer. St. Leonard’s Mill was established by Erskine Beveridge in 1851 and was the largest linen mill in Dunfermline. Several of our McGregor ancestors were hand loom weavers and who were later employed by Erskine Beveridge in the power loom mills.

David and Janet McGregor had twins, Margaret (1835-1908) and William (1835–1933), and two other children, Elizabeth (1842–1933) and David (1845–?). Margaret apparently was never married and had no offspring. Descendants of David are unknown and require further research. Some of Elizabeth’s descendants (surname Fraser) have been traced into the mid-20th century in Dunfermline. Our family descends from William McGregor who married Margaret Brown and who lived to the ripe old age of 97. Several articles in the Dunfermline Press give accounts of his long and interesting life. Two of William and Margaret’s sons, David (1864–1944) and James (1877–?) both immigrated to the United States in 1889 and 1897 respectively, and their descendants are well documented. The third son, William B. (1868–1945), made an extended visit to the United States in the early 1900s but otherwise lived his life in Dunfermline. William B. never married and had no children. William and Margaret also had two daughters, Jane “Jeanie” (1870–1829), who never married, and Janet (1875–?), who died young, according to family tradition. Of William and Margaret’s five children, only David was born in Dunfermline. The others were born in Antrim, Ireland, where the family lived for 17 years beginning shortly after son David’s birth, although they retained their Scottish heritage.

One Dunfermline Press article tells how, as a boy, the elder William McGregor played with Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919), the world famous philanthropist, who was also a Dunfermline native. Their respective parents were very well acquainted. A McGregor family story relates that when he first immigrated to the United States, William’s son David was offered employment by Andrew Carnegie (who immigrated in 1848 with his family), but being a proud Scot, David declined the offer.

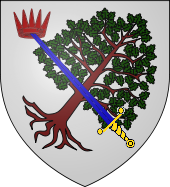

Clan Gregor Arms, Crest, and Tartan

Heraldry is the study of armorial bearings, including the art and science of devising and granting arms. Although there are technical distinctions, the terms armorial bearings, armorial devices, heraldic devices, heraldic achievement, arms, and coat of arms are all used broadly to describe a distinctive design on a shield and certain associated accessories. In many countries, tradition alone governs the use of armorial bearings by individuals, families, organizations, or governments. In some countries, most notably Scotland and England, laws strictly regulate the granting and use of arms, specifying for example that arms are always granted to an individual, never to a family. Although no such heraldic laws exist in the United States, persons of Scottish descent should respect the laws and traditions of Scotland, and never display as their own (or their family’s) the arms belonging to an entitled individual.

Armorial bearings were first used by feudal lords and knights in the mid-twelfth century on the battlefield as a way to distinguish allies from enemies. Other social classes later began to assume the use of arms for themselves. In Scotland, arms were treated as property and subject to inheritance from father to son or mother to daughter. Each individual who inherited a title to arms would make some change in color or add a distinguishing device or charge, called “differencing,” and submit an application for the new arms to the Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms, which dates from the 14th century. This would preserve the association of the armorial bearings with a particular family, while making the new arms granted to the individual unique and lawful.

Arms of McGregor individuals from the late 1700s onward often share several common elements: an oak tree (sometimes a pine) with its roots exposed, a sword, and a crown. The oak tree represents the legend that tells of Sir Malcolm Macgregor of Glenorchy, who lived in the mid-12th century, and how he saved the king’s life. Sir Malcolm was an attendant during the king’s hunting party. During the hunt, the king was attacked by an animal (often identified as a wild boar). Sir Malcolm recognized the king’s peril and asked if he could assist. The king replied “E’en do bait spair nocht” (“In what you do, spare nothing”). Sir Malcolm came to his aid and uprooted an oak sapling which he used to repel the boar. The king gave Sir Malcolm permission to use the oak tree eradicated (i.e., uprooted) in his crest in place of the fir or pine tree formerly used, and the king’s words were adopted as a clan motto.15 The bare tree roots of the arms are also said to represent the long period that the Macgregors were outlawed. The sword is a symbol of the Clan’s valor in battle, and the crown represents the Clan’s royal origins.

The current Chief of Clan Gregor is Major Sir Malcolm MacGregor of MacGregor 7th Baronet, 24th Chief of Clan Gregor. His official arms reflect the common elements described above, along with unique elements that make his armorial bearings distinctive from other McGregor arms. His blazon (i.e., description of arms) is: Argent, an oak tree eradicated in bend sinister proper, surmounted by a sword azure hilted and pommelled or, in bend supporting on its point, in the dexter canton, an antique crown gules.16 Translating the peculiar language of heraldry, his blazon means: a silver (argent) shield, an oak tree with exposed roots (eradicated) displayed diagonally from lower right to upper left as viewed by the wearer (in bend sinister) and in its natural form (proper), surmounted by a blue (azure) sword with a gold (or) hilt and pommel, displayed diagonally from lower left to upper right (bend), supporting on its point, in the right corner (in dexter canton), a red (gules) antique crown.

Unlike a coat of arms, which may only be displayed by the individual to whom they are granted, all clansmen and women are permitted to wear the Clan Chief’s crest encircled by a strap and buckle bearing the Clan Motto, as a display of pride and loyalty to the clan. The MacGregor Crest is described as: A lion’s head erased proper crowned with a five-pointed antique crown. The Clan Gregor’s motto, ’S Rioghal Mo Dhream — Royal is My Race — reflects the royal origins of the Clan Gregor from the House of Alpin. Another motto is also associated with Clan Gregor, E’en Do Bait Spair Nocht — In What You Do, Spare Nothing.17

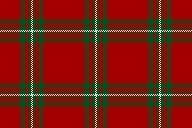

Clan tartans are a relatively modern invention. Many historians believe that clan tartans were not in widespread use at the time of the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Friend was distinguished from foe not through tartans but by the color of ribbon worn on the bonnet. The idea of men wearing the same tartan is thought to originate in military units in the mid-late 18th century. The naming and registration of clan tartans began in 1815 though the efforts of the Highland Society of London to solicit tartan samples from all clans. Almost all clans have several tartans associated with their name, and some tartans are declared as “official” by the clan chief.

Authority for registering and declaring official tartans is vested in the clan chief, and the Chief of Clan Gregor recognizes only four official Clan Gregor tartans:18

- Red and Black MacGregor Tartan: This tartan dates at least from the early 1600s and possibly earlier. It may have originated as a general tartan, not associated specifically with the MacGregors

- Red and Green MacGregor Tartan: Its exact origins are unknown, but it was in existence in the early 1800s. This is probably the most recognizable of the MacGregor tartans and is shown above.

- MacGregor of Glengyle/Deeside: This red and blue tartan dates from the mid-1600s and a specimen exists that is believed to date from 1750.

- MacGregor of Cardney: This tartan has been improperly called the MacGregor hunting tartan. There has never been a MacGregor hunting tartan. The MacGregors have never used dress, undress, dress down, fancy dress, hunting or any other such descriptions unlike other clans.

1Clan Gregor Society, website. The Clan Gregor Society was instituted in 1822 and is one of the oldest clan societies.

2Clan Gregor, Wikipedia website article.

3MacAlpin's Treason, Wikipedia website article, which cites two ancient documents. First, De Instructione Principus by Giraldus Cambrensis (known as Gerald of Wales), was written in Latin the late 12th and early 13th centuries. The first of three parts, called “Distinctions,” provides accounts of various events involving the Picts and Scots, including the event later called MacAlpin’s treason. Second, the Prophecy of Berchán, was written in the 12th century by an Irish abbot called Berchán. It is a large historical poem written in the Middle Irish language. The poem is very indirect in its identification of Scottish kings, but the Scottish kings spoken of can be identified, and the poem is one of the most important sources for early Scottish history.

4Kenneth MacAlpin, Wikipedia website article

5The Clans of Sìol Alpin, website.

6Family Tree DNA, website.

7Clan Gregor, Wikipedia website article.

8Travel Scotland- the Scottish Clan System, website.

9Clan Gregor Society, website.

10The Dean of Linsmore’s Book, by Thomas M. M’Mauchlan with additional notes by William F. Skene, 1862. Digitized copy available at Google Books.

11The Highland Clans, Volume II, by William F. Skene, 1837. Digitized copy available at Google Books.

12Dunfermline Abbey, Wikipedia website article.

13History of the Clan Gregor, by Amelia Georgiana Murray MacGregor, 1898. Digitized copy available at Google Books.

14Journal of the International Music Society 1904-05, Volume 6-7, page 244. The journal is written in German but this article is in English. Digitized copy available at Google Books.

15The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales by Sir Bernard Burke, 1884, London. Digitized copy available at Google Books.

16Clan Gregor Society, website.

17Clan Gregor Society, website.

18Clan Gregor Society, website.